I. Introduction

In recent years, data security and/or data transfer have become a burgeoning concern in many jurisdictions around the world. For example, since 1 October 2022, the penalty for non-compliance with the Singapore’s Personal Data Protection Act will be lifted to up to 10% of local annual turnover for organizations whose turnover exceeds S$10 million. At the same time, several laws and regulations for data security or data transfer have been implemented in the People’s Republic of China (hereinafter referred to as the “PRC”), such as the Data Security Law of the PRC (hereinafter referred to as the “DSL”), which came into force on September 1, 2021. The DSL can be treated as another pillar of legal framework on data security and/or data transfer, besides the Cyber Security Law of the PRC (hereinafter referred to as the “CSL”), and the subsequent Personal Information Protection Law of the PRC (hereinafter referred to as the “PIPL”), etc.

Against this backdrop, recently, Wang Jing & GH was instructed to issue a legal opinion on issues concerning China’s laws and regulations governing cross-border data transfer. Our client is a Chinese national residing in the territory of the PRC. The Company, of which the client is a director, was involved in a legal proceeding as the Respondent in the British Virgin Islands Court (hereinafter referred to as “BVI”). The Claimant in the BVI proceeding brought a contempt proceeding against the Company and two directors of the Company, and the two directors were faced with a potential request to attend the BVI Court hearing remotely and provide relevant evidence to the BVI Court.

Since the evidence potentially sought by the BVI Court may contain data stored in the territory of the PRC, for example, some records of communication between the Company and the Chinese administrative bodies, and given that a few new PRC laws and regulations on data protection were promulgated and became effective in the past few months, the client was concerned with and thus sought our advice on the lawfulness of responding to the BVI Court request under the current legal regime.

In legal context, the above issues can be summed up to be the requirements for an individual to provide data stored in the territory of the PRC to foreign authorities, specifically for civil proceedings, and if the individual has crossed the PRC border physically (e.g. to Hong Kong) with the data in hard copy, whether the aforesaid requirements can be avoided.

II. Analysis

i. China’s Restriction on Cross-border Data Transfer

1. Approval Requirement for Compulsory Data Transfer to Foreign Authorities

The restrictions on evidence taking for civil litigation purposes were often overlooked until the recent shift of focus to the “war of data” between countries. The relevant requirements for approval of data transfer to foreign authorities can be found in Article 36 of the DSL, effective on September 2021, and the PIPL which became effective two months later. Article 36 of the DSL stipulates that the approval of the competent authority of the PRC is the precondition for providing data stored in the territory of the PRC in response to requests from any foreign judicial or law enforcement authority. The stipulation in Article 41 of the PIPL is literally the same. It seems that Chinese laws impose restriction in the same manner on all cross-border data transfers requested by foreign authorities regardless of the type of cases.

Since there is no explicit mention of the circumstance where an organization or individual voluntarily provides the data stored in the territory of the PRC, it can be reasonably assumed that the approval requirement may not apply to such circumstance. Nevertheless, in the case of a cross-border data transfer, the organization or individual should comply with other related rules.

Concerning criminal cases, in comparison, most jurisdictions, so does the PRC, have enacted specific laws which strictly limit the criminal activities conducted by foreign authorities. For example, Article 4 of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on International Criminal Judicial Assistance provides that in respect of evidence-taking, no institution, organization or individual within the territory of the PRC may provide evidentiary materials and assistance prescribed by this Law to foreign authorities without the approval of the competent authority of the PRC.

2. Security Assessment Requirement for Cross-border Data Transfer

Besides the approval requirement for compulsory data transfer when the recipient is a foreign judicial or law enforcement authority, a data transfer should also be subject to the security assessment requirement designated for some special data categories. This seems to be the stance of two new regulations which have not yet become legally effective, i.e. the Internet Data Security Management Regulation (Draft for Comment) and the Measures for Evaluating the Security of Transmitting Data Overseas (Draft for Comment). Article 39 of the aforesaid Regulation and Article 4 of the Measures both stipulate the approval and security assessment requirements for cross-border data transfer. But since neither the Regulation nor the Measures are effective for the time being, in this article we will only discuss the security assessment as a parallel requirement according to the data categories.

(1) Types of Data Transfer Out of the PRC Requiring Security Assessment

Pursuant to the DSL, the PIPL, the CSL, the Measures for Evaluating the Security of Transmitting Data Overseas (Draft for Comment) and other relevant laws and regulations of the PRC, security assessment is required for the following main types of data:

A. Important Data Collected and Generated by Operators of Key Information Infrastructure During Their Operations in the Territory of the PRC

Key information infrastructure is defined as critical information infrastructure in important industries and fields such as public communications and information services, energy, transport, water conservancy, finance, public services and e-government affairs and the critical information infrastructure that will result in serious damage to state security, the national economy and the people’s livelihood and public interest if it is destroyed, loses functions or encounters data leakage (Article 31 the Cyber Security Law). The specific rules governing transfer of such data should be developed by the competent authorities and administrative departments according to the division of functions prescribed by the State Council (Article 32 the Cyber Security Law).

According to Article 37 of the Cyber Security Law, security assessment shall be conducted in accordance with the measures developed by the national cyberspace administration in conjunction with relevant departments of the State Council if it is indeed necessary for critical information infrastructure operators to provide personal information and important data to overseas parties due to business requirements. Furthermore, Article 31 of the DSL stipulates that the security management of cross-border transfer of important data collected and generated by operators of key information infrastructure during their operations in the territory of the PRC shall be governed by the Cyber Security Law.

Further, according to Article 4 of the Measures for Evaluating the Security of Transmitting Data Overseas (Draft for Comment), where a data processor is to transfer abroad personal information and important data collected and generated by the operator of critical information infrastructure, it shall apply for security assessment through the local provincial cyberspace administration at the place where the data processor is located.

B. Important Data

Article 30 of the DSL provides that a processor of important data shall conduct regular security assessment and Article 4 of the Measures for Evaluating the Security of Transmitting Data Overseas (Draft for Comment) is a supplement to the security assessment for important data.

C. Personal Information

a. Cross-border transfer of personal information, for business or other needs, should pass the security assessment organized by the national cyberspace administration. (Article 38 of the PIPL)

b. If critical information infrastructure operators and the personal information processors that process personal information reaching or exceeding the threshold specified by the national cyberspace administration in terms of quantity wish to transfer information outside of the PRC, such transfer should also pass the security assessment by the national security administration. (Article 40 of the PIPL)

c. Article 4 of the Measures for Evaluating the Security of Transmitting Data Overseas (Draft for Comment) contains more specific requirements, according to which, where a personal information processor who has processed personal information reaching one million persons, or has provided accumulatively personal information of more than 100,000 persons or sensitive personal information of more than 10,000 persons to overseas parties, wishes to transfer personal information abroad, the processor shall apply for security assessment to the national cyberspace administration through the provincial cyberspace administration of the place where the processor is located.

Apart from the data mentioned above, the national cyberspace administration may also require security assessment for the transfer of other data.

(2) Security Assessment Procedures

To comply with the security assessment cited above, two Drafts for Comment can be referred to although currently they are not yet effective, as they reflect the future legislation trend.

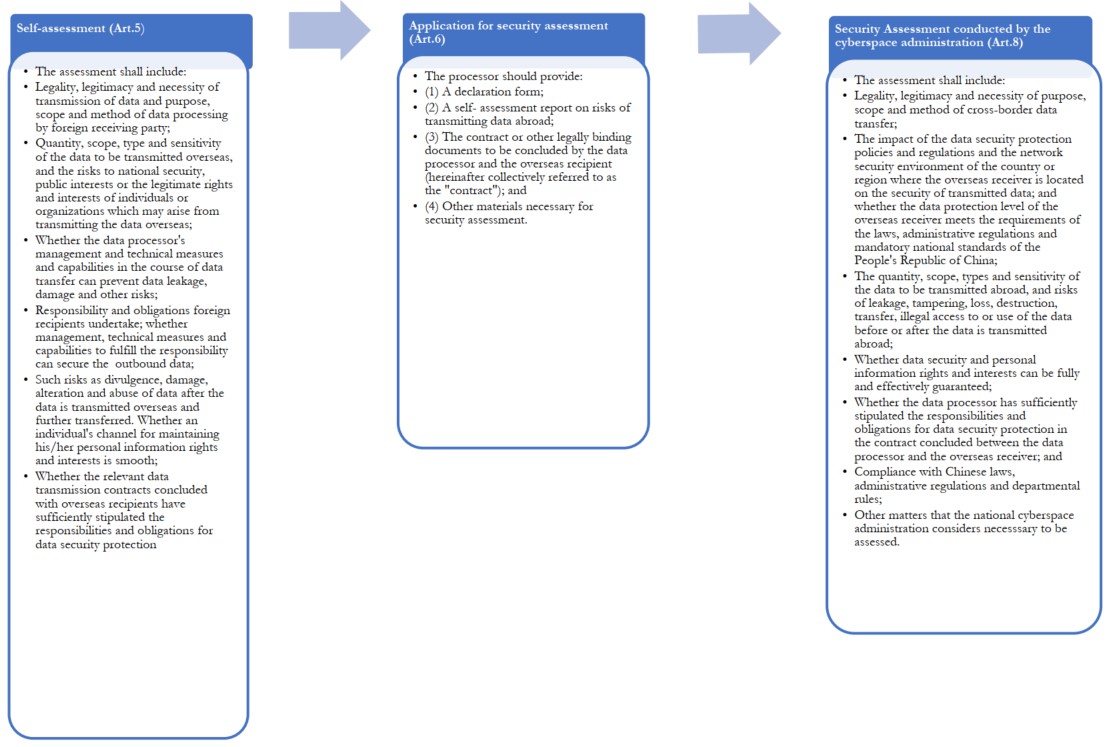

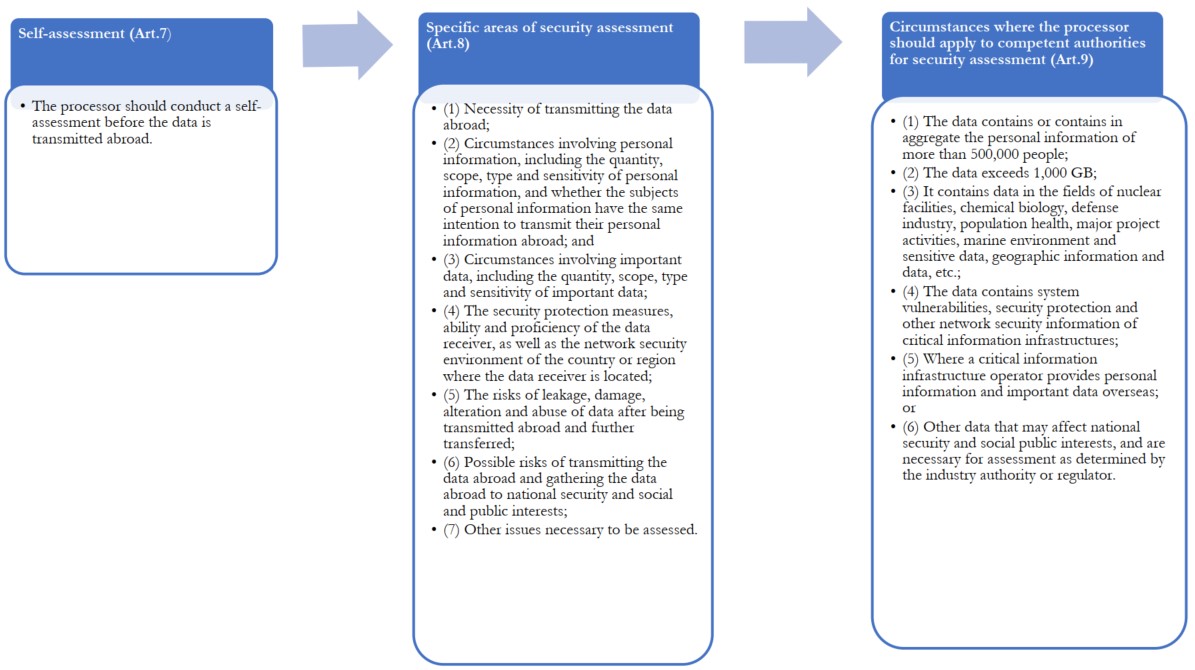

A. Measures for Evaluating the Security of Transmitting Data Overseas (Draft for Comment)

B. Measures for Evaluating the Security of Transmitting Personal Information and Important Data Overseas (Draft for Comment)

(3) Other Restrictions on Cross-border Data Transfer

A. Control on the Subject: Data Related to National Security

a. Data that matters to national security, the lifeline of national economy, important aspects of people’s livelihood, or material public interest, among others, shall be national core data subject to a more stringent management system. (Article 21 of the DSL)

b. The data related to national security should go through an independent security review according to the state data security review system. (Article 24 of the DSL)

c. The export of such data (safeguarding national security and interest and performing international obligations) would be controlled by the state. (Article 25 of the DSL)

The rationale behind the aforesaid legal provisions is to protect data security at the national level. Therefore, the data under this category can hardly pass the stringent review and be transferred abroad.

B. Control on the Object: Personal Information cannot be Transferred to the Entity or the Region which harms the national security and public interests of the PRC.

a. For any overseas organization or individual that engages in personal information processing activities which damage the rights and interests relating to personal information of citizens of the PRC or compromise national security or public interests of the PRC, the provision of personal information to it or him will be prohibited or restricted. (Article 42 of the PIPL)

b. If a country or region adopts any prohibitive, restrictive or other similar discriminatory measures against the PRC in terms of personal information protection, the PRC would conduct reciprocal measures against the aforesaid country or region in accordance with the actual circumstances. (Article 43 of the PIPL)

To sum up, for compulsory data transfer in response to the disclosure request from a foreign authority, the transfer should firstly be approved and be compliant with other control measures (i.e. limits on the export or security assessment) according to the category of the data.

ii. If the data to be transferred is not stored in the territory of the PRC, whether the relevant requirements still apply?

If the person who is subject to the request of the BVI court for information disclosure does not reside in the territory of the PRC and possesses the relevant information in hard copy, and eventually made the data transfer, it seems like a roundabout way to avoid the aforesaid various approval or security assessment requirements. However, one should know the extra-territorial application of the PIPL and the DSL. For example, according to Article 3 of the PIPL, this Law shall also apply to the processing outside the territory of the PRC of the personal information of natural persons within the territory of the PRC if the information is processed for the purpose of providing products or services to natural persons inside China, or to analyze or assess the conduct of natural persons inside China, or under any other circumstance as provided by any law or administrative regulation. Similarly, in the DSL, Article 2 extends the application of the DSL to the data processing activities which are conducted to the detriment of the national security, public interest, or lawful rights and interests of citizens and organizations of the PRC and holds the processors liable. Thus, in the scenario described above, although the data has been physically brought outside the territory of the PRC, there still exists the risk of such data being regulated, especially when there is a “bottom-line” rule (“under any other circumstance as provided by any law or administrative regulation”).

iii. Conclusion

In conclusion, the cross-border transfer of data stored in the territory of the PRC to a foreign authority must first be approved by the competent PRC authorities, and then comply with other applicable requirements depending on the category of the data. We would suggest that domestic organizations and individuals should follow the regulations and/or laws mentioned above to provide data to foreign judicial or law enforcement authority with the approval of relevant authorities. Non-compliance with the said approval requirement and other applicable requirements may induce serious consequences. In accordance with Article 48 and Article 52 of the DSL, and Article 66, Article 69, Article 71 of the PIPL and other relevant rules, if a domestic organization or individual provides data stored in the territory of the PRC to any foreign judicial or law enforcement authority without the approval of the competent authority of the PRC, the domestic organization or individual may face significant penalties including financial penalties of up to RMB5 million.

There is no doubt that there are more restrictions on cross-border data transfer and the penalties for non-compliance with relevant laws and regulations are higher than before. For example, recently the Office of Cybersecurity Review conducted cybersecurity review of China’s online car-hailing platform giant Didi for data security concern. Therefore, we strongly recommend that companies and individuals that may transfer data collected in the PRC abroad closely monitor the development of the relevant legal regime of the PRC, and seek legal advice from PRC counsels before making cross-border data transfer.

Finally, we are also delighted to share with you the latest market recognition and law award nomination we received. Recently Guangzhou Lawyers Association officially announced a list of “Guangzhou Leading Lawyers in Foreign-related Practice”, where our managing partner Mr. Wang Jing, partner Mr. Wilson Wang, and senior associate Ms. Bai Xiaoliu were included in recognition of their expertise and experience in foreign-related practice. Furthermore, Wang Jing & GH was nominated for South China Law Firm of the Year by SSQ ALB China Law Awards 2022.

If you require more information on shipping laws in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic or legal advice on related disputes, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Author: Wang Jing, Alicia OU, Christy TANG